In this series of blogs we will be looking at a number of issues, practical examples and tips for setting up social action projects rooted in therapeutic principles. One of the aims is to encourage colleagues to focus on their own social justice initiatives and to regain a sense of control on the positive impact they could have now and in the future. Here are some of the titles:

- The beginning – Why?

- Values, Ethics and Boundaries

- Public sector or third sector?

- Management and Legal

- Money

- Therapeutic and dynamic model of administration

- Maintaining the frame

- Maintaining compassion

- The people – Who does it take? and What does it take?

- Reflective Projects

- The Social Response Cycle

- Endings

BLOG 1

The beginning – Why?

Introduction

Setting up, establishing and maintaining a project can feel overwhelming. Some of the skills needed for setting up a social action project are within the skills repertoire of trained counsellors and therapists. Some are different. But social action projects that survive tend to be ones that are able to engage in collaborative reflection with the unknown and with changing contexts. Therapeutic thinking is particularly useful for considering issues which can be found at the heart of social action projects – change, relational dynamics and power differentials.

Why am I writing about social action projects? We often talk about social justice and social action in the world of psychological therapies. Against a backdrop of global issues and unrest it can be hard to feel anything but helpless in the face of the challenges. There are books written about social action and social justice with titles like Psychology and Social Change, Social Justice, Mental Health and Therapy. Social justice features in psychotherapy and counselling training curricula. But there still exists a learning gap about setting up social action projects within the context of psychological therapies. How do you actually go about it?

Of course, there is no definitive answer for how to set up social action projects. But you have to begin somewhere so some pointers and examples from experience are a start.

Motivation and relevant skills

Let’s think about what motivates us to set up a social action project rooted in therapeutic principles. What is the motivation for going beyond the therapy room. It could be the case that you work with very vulnerable populations. You are aware that they have so many more unmet needs than therapy can attend to. The temptation is often to go beyond the frame of therapy. Is this to satisfy your need to act on your own frustrations? If that desire dovetails with what potential beneficiaries need then that motivation may be a good fit. But, taking the position of a rescuer or saviour can be very seductive. It can lead us to pick and choose the boundaries we want to adhere to and those we don’t. To really understand what is driving us requires a deeply honest audit of our motivations and needs. We may find that what we want to do and what beneficiaries really want and need is not a good match. (We will consider ethical considerations such as the beneficence – autonomy continuum in a later blog). But, if we find that it is a good match, we can make decisions and take action that is thoughtful, accountable and collaborative, and that may involve us in initiating something new which could be an overtly therapeutic service or an initiative that is underpinned by therapeutic ways of thinking and behaving.

Manivong Ratts a professor of counselling at Seattle University is one of the authors of A set of guidelines for the counselling profession, published in the USA.

To quote these guidelines:

“Effectively balancing individual counseling with social justice advocacy is key to addressing the problems that individuals from marginalized populations bring to counseling. Certain situations will call for individual counseling. Other situations may require interventions that take place in the community. The challenge, therefore, is knowing when to work in the office setting and when to work in the community realm.”

Ratts suggests that finding the balance between practice which takes place in the consulting room and practice in the wider social frame, is a skill of assessment. The skill of assessment is crucial for this work (as we will see in a later blog which describes the model of the Social Response Cycle https://www.bacp.co.uk/cpd/social-response-cycle-member-resource/). What other skills do you have already and which might you need to develop?

Skills you probably have:

- Honest and authentic communication skills

- Reflective practice skills

- Empathy

- Ethical decision-making

- Self-care/compassion

Skills you may need to develop:

- Leadership (the buck stops with you)

- Assessment

- Facilitation

- Developing a compassionate relationship with your own authority

- Ethical Decision-making as a leader

- Financial literacy

- Collaboration

- Delegation

- Assessment

- Entrepreneurship – vision

- Cautious risk-taking

- Assessment

- Responsiveness and Adaptability and Purpose and focus

- Embracing inadequacy

My experience – Influences and inspiration

I started by learning from and being inspired by many different people’s experiences and models. One of those people was Sue Holland, a psychotherapist working in the White City Housing Estate in London in the 1980s with women who had been abused. Holland’s psychotherapy and social action project took individual treatment into action, encompassing the women’s sociopolitical circumstances and empowering the women to deal with their distressing experiences both individually in therapy, and socially by taking action.

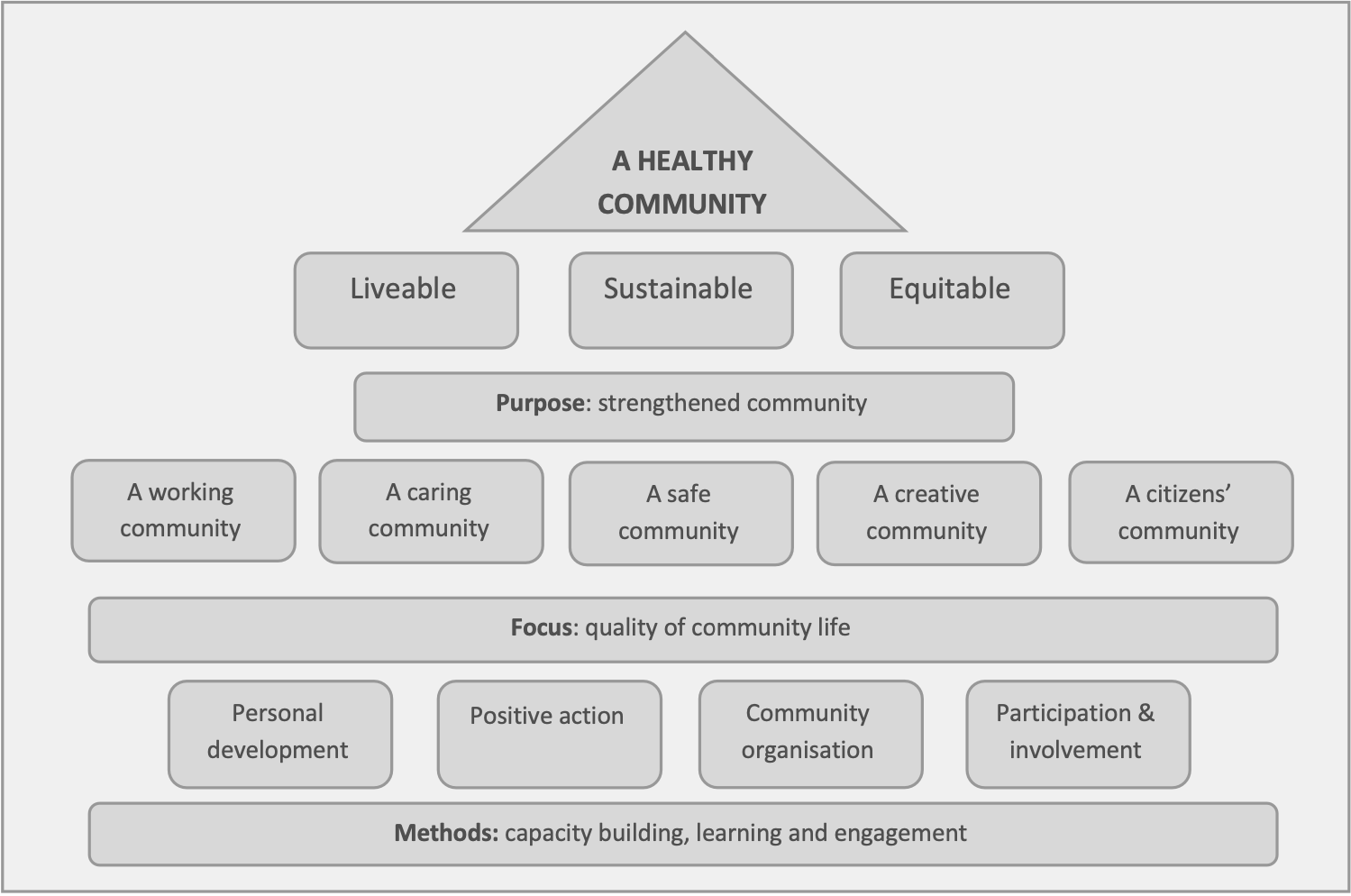

I was also inspired by initiatives in community development, for instance Barr and Hashagen’s ABCD framework for improving community development. They viewed community development as a question of empowerment which improved community life, leading to strengthened and healthy communities.

My experience – setting up a social action project

I am going to use a case study from my experience to illustrate the setting up of a project which was inspired by the work and models of people like Holland, Barr and Hashagen. This example is of a registered charity, Mothertongue multi-ethnic counselling service (2000 – 2018). Mothertongue was a community psychological therapy service which offered free, culturally and linguistically sensitive counselling for people from multi-ethnic communities in their preferred languages. I describe how Mothertongue came into being, what enabled it, the challenges it faced and how that might link with today’s issues. Are there lessons that have been learned that can apply to today’s social context? How is the current landscape different and what new responses are required? As you are reading you might notice if any of the skills I mentioned earlier are demonstrated in this account.

I was working at a Multicultural WEA (Workers Educational Association) in Reading as a teacher while finishing my training as a psychotherapist in the late 1990s. I had become increasingly aware that my students had much in common with many members of my family who in the 1970s and 1980s spoke no or little English and who had had painful and distressing experiences. Like them, the students at the WEA had nowhere safe to talk, where they would be understood and where they could find support. Here we were at the end of the 20th century still without any suitable provision for people in similar circumstances. I’d been involved with the voluntary sector in Reading for a while and I talked to Catherine, the local voluntary sector development worker for Reading, as well as my colleagues at the WEA, about the lack and the gap in services to support people, for whom English was not their first or heritage language, with their mental health needs. And it seemed to touch a nerve. It seemed that other practitioners had encountered similar situations. Catherine felt there was enough energy around for it to be worth calling a public meeting.

You may be wondering like I did, “What does she mean – a public meeting?” I didn’t have any idea what she meant, how to go about it or who would come, but luckily Catherine did. And that is where collaboration was so important right from the start of this endeavour. Catherine could call on the voluntary sector partnerships with the Citizens Advice Bureau, Health commissioners, Race Equality organisations, politicians and others. We called a public meeting and 36 professionals, practitioners, managers, commissioners, local authority councilors and an MP attended.

We achieved one of our desired outcomes at this meeting. Eight people volunteered to become Steering Group members of Mothertongue. Over the next two years that steering group met every month. We achieved charitable status, put our policies and procedures in place and we obtained a small pot of funding to set up a pilot Mothertongue service.

Obtaining small pots of money to do small, pioneering pilot services became our methodology of action. This is described in the Social Response Cycle (SRC) https://www.bacp.co.uk/cpd/social-response-cycle-member-resource/ which I will describe in a later blog. The methodology became the hallmark of our development and project delivery for almost 20 years. From the pilots we were able to collect evidence of successfully meeting needs (or not). The process of offering a service at the same time as investigating its efficacy was based on a relationship of reciprocity and the belief that data does not justify the service, the service provides the data[1].

So, with the data and the evidence we had collected we made funding applications to provide a fuller service. Our funding success rate was 80%. We made it easy for funders to choose to support us. It was hard to ignore the evidence which we had gathered from real world initiatives. We used this process (the SRC) for the Counselling Service, for our own Mental Health Interpreting service, for our Relationship Counselling Service, for our Knitting Group and for our Art Group with newly arrived students in schools with very little English etc.

Any one of those projects on their own was significant in its own right. I am convinced that very small initiatives that DO something, maybe providing a service where there is a gap, can have a disproportionately large impact. It can feel disheartening, in the face of immense need, to embark on a small initiative. It feels inadequate. However, when many very small projects, each of which may be inadequate on their own, are considered cumulatively, they make something substantial that is difficult to ignore. In fact, the tendency to “scale up”, to enlarge and expand small effective projects is often counter-productive. It may increase the width of a project but at the sacrifice of the depth of connections and relationships. I will return to this idea in later blogs.

Mothertongue remained a small organisation. We were a close, caring and compassionate community, united by our shared values and focus. Some projects of this type might describe themselves as a family. We described ourselves as a community. That was our frame. Of course group dynamics will occur whenever clusters of people come together. In a family everyone’s personal histories, responsibilities to each other, disputes and alliances are in the foreground. But I think it is more helpful to think of the frame for a group that has formed to work in the service of a target beneficiary as a caring and compassionate community of adults rather than a family.

You may be thinking that some of the details I have just described may be very specific to a time and a place. Here are some recent examples of setting up projects initiated and developed by others:

Chai and Chat – a Women’s craft group in the community in Glasgow https://thewell.org.uk/women-at-the-well/

Let’s Interpret – offers training and peer support for bilingual and multilingual women living in Cardiff https://www.letsinterpret.org.uk/

The Social Response Cycle has been applied via Pásalo and Mothertongue to a variety of projects including:

- The Mental Health Interpreting Service

- A place to belong – art workshops for newly arrived children in schools with limited English proficiency – A Knitting Group

- Anthologies of interpreters, therapists and clients about their experiences in therapy across languages

- Funding for supervision/Apprenticeship model for interpreters with ongoing evaluation

- The Bilingual Forum for Therapists and Mental Health Interpreters

- Colleagues Across Borders – A project which for 11 years has been matching psychotherapists, psychologists and counsellors and others, with refugees in the Middle East/Southwest Asia, who have recently trained as psychosocial workers. The offering is an online buddying, collegiate, mentoring relationship. The project operates successfully with zero funding.

- Commissioned and Produced ACE funded Play – The Soho Theatre The Session – Performance Ethnography (Denzin N, 2003)

- E-learning module BACP “Therapeutically framed social justice initiatives” https://www.bacp.co.uk/cpd/social-response-cycle-member-resource/

- Book – Other Tongues: psychological therapies in a multilingual world (June, 2020)

- 2021 – E-Learning resource: Multilingualism and mental health funded by the Paul Hamlyn Foundation. Free for all practitioners. https://www.pasaloproject.org/multilingualism-mental-health-and-psychological-therapy—course-content.html

- 2024 Tuning In – an anthology of creative writing about the unheard experiences of multilingualism in psychological therapy.

Summing up

I have emphasised the need to understand your motivation because motivation is the essential fuel that powers social action projects which are therapeutically framed. I have found that when I feel disheartened at times, in the midst of a project, reconnecting and committing to my motivation gives me the energy to keep going. Alongside motivation I suggest that we need to understand and develop compassion for inadequacy and our responses to inadequacy.

I have tried to give a range of examples of projects but you may be interested in setting up projects in other contexts. I hope I have managed to encourage you to feel that you can make a start and do something, no matter how small or how inadequate you feel. I know that a sticking plaster is no kind of solution. But I also know that a sticking plaster can prevent infection. Why wouldn’t you want to act on that?

Of course, taking action requires courage. So I am also suggesting that while you need to be prepared to take risks (cautiously), it is important to remember that our professional frames are there to support us. To help navigate cautious risk-taking we need to have confidence in, respect and trust for the professional frames within which we work. The frames are there to protect us and to protect the people we serve. We will be considering the frame with particular reference to ethics and boundaries in the next blog.

I will finish with a reminder from the anthropologist Maragaret Mead:

“Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed it’s the only thing that ever has.”

You may not be able to change the world on your own but multiple micro social justice initiatives can form part of a jigsaw for greater social change and impact.

We have recorded a series of conversations about setting up social action projects. We discuss some of the points raised here as well as other issues. This link https://onlinevents.co.uk/courses/the-beginning-why-building-maintaining-therapeutic-organisations-workshop-with-beverley-costa/ allows you to access the recording of the conversation which relates to this blog. (Please note there is a small cost to access the recording though Onlinevents).

References

Barr, A. and Hashagen, S. (2000). Achieving Better Community Development Framework ABCD Handbook: A framework for evaluating community development. London: Community Development Foundation

Holland, S. (1992). From social abuse to social action: a neighborhood psychotherapy and social action project for women. In J. Ussher & P. Nicholson (eds), Gender Issues in Clinical Psychology. London: Routledge

Ratts, M. J., Singh, A. A., Nassar‐McMillan, S., Butler, S. K., & McCullough, J. R. (2016). Multicultural and Social Justice Counseling Competencies: Guidelines for the counseling profession. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 44(1), 28-48.

[1] Formal research projects which collect data are often conducted at the expense of practice. The financial cost of formal research projects (frequently conducted by universities and other institutions), the nature of knowledge and the prestige attached to different types of evidence are all considered in subsequent blogs.