Frequently, social action projects seek to address gaps in public service provision. Projects can, understandably, feel that the public sector should fund them to do the work that public services should be doing.

However, small NGOs are in a different position from public services for a number of reasons. For instance, they have a level of flexibility that public sector organisations do not. That puts them in a position to respond more speedily and effectively to social needs.

Funding is always an issue for small organisations. But if accepting the funding means your project ends up becoming a mini-public sector organisation, should you turn down an offer of funding from the public sector? It is hard enough to get them to acknowledge what you are doing in the first place! Is it ethical to take the money. Is it ethical not to?

This conversation links with the fifth blog on Money Matters.

A voluntary or third sector initiative may be set up with the intention of addressing a gap in public sector provision. Working with the public sector to deliver services involves a complex network of interconnecting relationships. It can be very confusing. Not least because of the variety of terms that are used to describe the two sectors.

Here is a selection of terms that refer to non-governmental organisations: third sector, voluntary sector, civil society, or community sector.

As far as I can tell, they all mean the same thing.

There are, though, differences between public sector (also known as the statutory sector) services and third sector services.

Public sector services are organisations generally funded by national or local government often to provide statutory services. Public services include local council services such as Social Services, Education, Policing, Environmental or Health Services.

The third sector on the other hand, is independent of national and local government. It represents a collection of non-profit organisations that work to create social impact, rather than profit. These organisations include: registered charities, community groups, community interest companies (CICs), social enterprises, cooperatives and research institutions. In order to be classified as a third sector organisation the following three conditions must be fulfilled. Organisations must be:

- Non-governmental: they cannot be owned or controlled by the state

- Not for profit

- Values driven

We will say a bit more about legal structures in our 4th Blog on Management and Legal Issues but here are a few key issues:

- Social enterprises or CICs earn money by selling products or services, and they reinvest profits into their business.

- CICs are social enterprises which are registered and regulated as limited companies by Companies House. Theyaim to benefit the community rather than private shareholders. They are subject to lighter regulation than a charity but they may not be eligible for all types of funding.

- Charities are subject to charity law, which is set out by the High Court. They rely on donations and grants to fund their activities. They don’t make a profit.

Charities and CICs share similar purposes:

- Charities are set up to achieve a charitable purpose, which benefits the public.

- CICS are set up to improve communities, environments, life chances, and tackle social problems.

Organisations in the third sector may consider various factors before deciding on the appropriate structure for them. One of the most significant factors that will influence the decision concerns funding. A charity has access to a greater range of funding opportunities than a CIC. But both are often eligible for support from the public sector.

It is tempting to think that the public sector should pay for a service which is addressing a gap and the needs of communities that it can’t meet itself. For example, doctors, nurses, and social workers may refer people they can’t/don’t have the capacity to help to a third sector organisation. So why shouldn’t the third sector organisation receive renumeration? It is often the case that local public sector services and commissioners recognise that third sector organisations are trusted by communities that do not trust the public sector. Third sector services and organisations can respond faster and with innovative solutions to longstanding issues that the public sector has failed to tackle. Public service commissioners may value what the third sector can achieve and may offer funding.

It is understandably tempting for an organisation to accept public sector support when it is offered. But public sector support can come at a price. Ironically, public sector funding often comes with conditions that inhibit third sector organisations from reaching the communities and addressing the gaps they were set up to address.

Public sector commissioners and funders can end up unintentionally creating a mini-public service out of a small third sector organisation. Is that in the organisation’s interest?

If accepting funding means your project ends up becoming a mini-public sector organisation, should you turn down an offer of funding from the public sector? Is it ethical to take the money. Is it ethical not to?

Let’s pause for a moment and consider the place played by power when we are considering public and third sector contexts. Clearly a funder has a great deal of power, particularly if you need their funding. But you also have power as a third sector organisation.

Unfortunately some statutory funders can misuse their power. They can (often inadvertently) use bullying tactics – even if the bullying takes a subtle form. Here are some examples:

- Suddenly giving you very short notice of a condition you need to meet

- Giving you an offer of payment and then reducing the amount after you have accepted the offer

Here is an illustration of what happened to a small third sector service we will call Turn Around when they were offered funding from a government department. The name of the organisation and other identifying features have been changed for confidentiality reasons.

Change of funding offer

Turn Around applied for funding, carefully following the guidelines provided. They had put together a thoroughly costed budget and they were delighted to hear that their funding bid for a three-year project was successful. A week before they were due to receive payment and to start the project the government department, that was administering the funding allocation, informed Turn Around that they had changed their minds and had decided they wanted to spread the money across two additional organisations. They wanted Turn Around to reduce their budget by £20k for each of the three years of the funding period. This was obviously not very satisfactory for the organisation. But they decided they could manage if, rather than reducing the money per year, they reduced the duration of the project. They suggested that they would start the project later (by 6 months), which would shave £60k (the equivalent of 3 x £20k) off the total budget. Initially the government department refused to agree to this suggestion but Turn Around told the government department that to do as they wanted would make the project unsafe. The government department had the power to change their mind because they had the money. But Turn Around had the power of their expertise about client safety. They were able to negotiate and arrive at a compromise that was reasonably satisfactory for all.

A funder can dictate terms but do you need to accept them all? What about your terms?

When you receive funding you are often required to sign Service Level Agreement (SLAs) and contracts. These agreements offer protection. Frequently those protections are for the dominant party which is offering the funding e.g. the Health Service, the Local Authority, a university. They are often not so careful about the protection of the less powerful parties of the contract – i.e. you!

But don’t forget you do have power. The public sector wants what you can offer. You have a right to have protection in the SLA too. That means things like having your core costs met, not being subject to spot purchases, not having to do things with very little warning, having your expertise respected, owning your intellectual property.

Counterintuitively it is important and ethical not to be persuaded to expand your service unless this is already part of your strategy. If you are going to be stretched beyond your capacity, the ethical decision is not to expand. Big is not necessarily better and multiple small initiatives are often more effective and (something which big organisations find hard to believe) much more cost effective.

How do you hold on to the power and the agency you have in the third sector so that you can set some of your own terms?

The third sector has a number of features which the statutory sector needs

- Independence

- Agility

- Services which address inequity and social justice

- Responsiveness

- Ability to tolerate some risk

- Access to marginalised communities and neglected populations

- Good outcomes with neglected communities

- Specific expertise

These are all what the public sector wants. Don’t give it away!

Another way in which you can gain power is by diversifying your funding streams. You can get funding from e.g. Trusts, Foundations, The National Lottery – some of these may align better with a third sector organisation’s values. It is a good idea not to be funded completely by the public sector. Although there is competition for these kinds of funds I strongly recommend having a strategic approach to funding, from the beginning, and a willingness to accept that the process of writing funding bids goes with the territory of a third sector service. (I know. It is so time consuming but it really is essential if your beneficiaries are going to get a good service). At Mothertongue, we were able to respond to financial bullying because we achieved diverse funding (as set out in our funding strategy). We never allowed the local public service funding to rise above 30 per cent of our total income. The other funders (who represented 70 per cent of our income) valued the independence that we had as a non-governmental organisation. The public sector funders were aware that they could not impose constraining terms and conditions without jeopardising the other funding and ultimately, our survival. Ironically, that vulnerability was our strength.

Points to remember

- Think about your position with regard to power and agency (you may have more than you think!) [1]

- Include a diverse approach to funding streams in your funding strategy

- Don’t be seduced by e.g. short term funding to increase your service which will leave you stranded at the end of the short term

- Don’t be bullied by public sector agendas that are not your agenda

- Don’t introject the public sector’s anxieties. Protect your staff and your beneficiaries from public sector anxieties

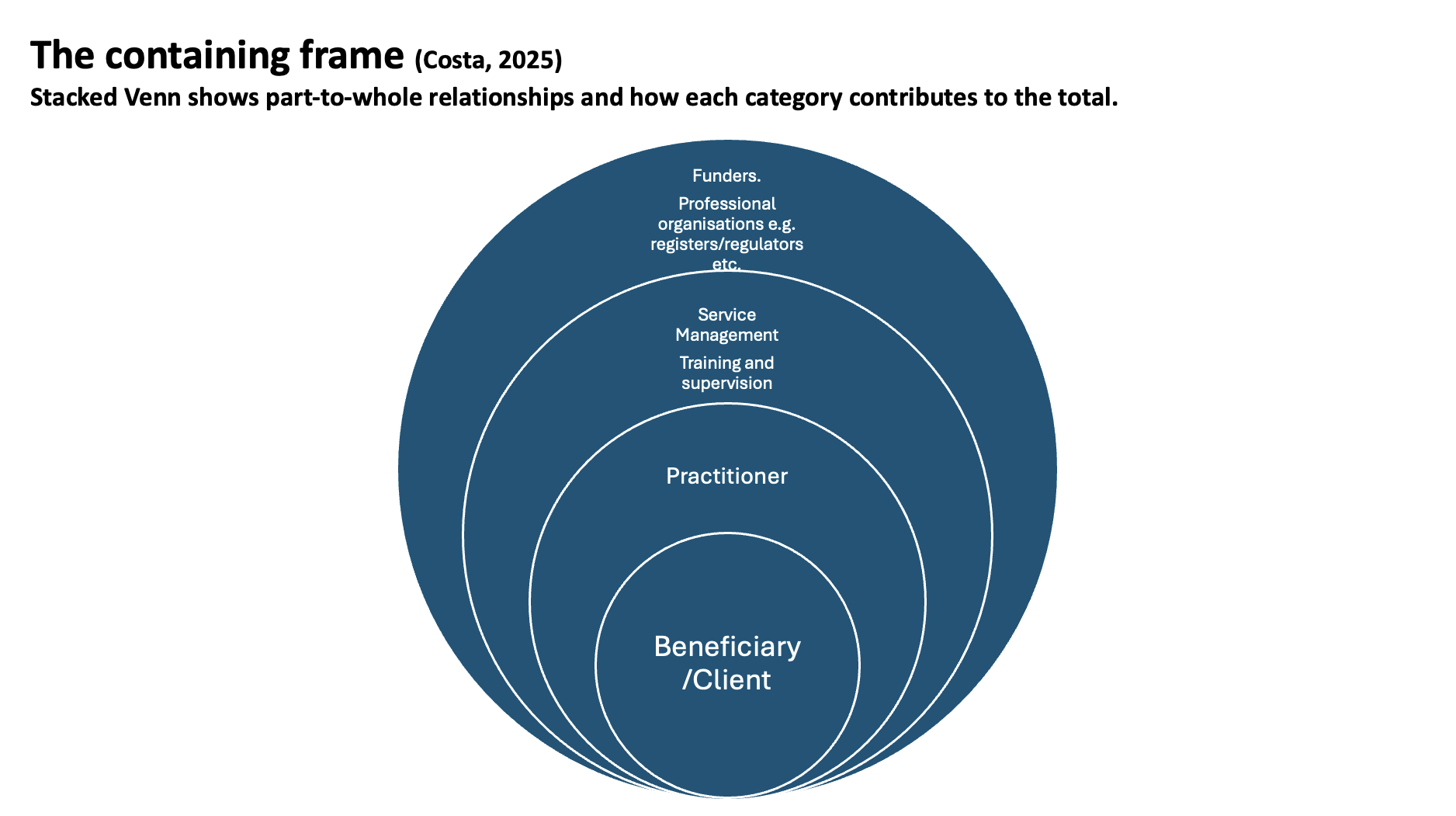

This blog may give the impression that power struggles between the public and third sectors are inevitable. They don’t have to be, though. When care is taken to consider the different points of view of everyone involved (from both the public and voluntary sectors) and everyone is committed to prioritising, over all the other demands they face, the best outcomes possible for beneficiaries, then more effective and efficient outcomes are possible. The containing frame is an example of the way in which we can work truly collaboratively together to create connected and interdependent systems, which connect with all the relationships in the system. including funders, and where are all able to hold each other to account. It is a frame where we look after each other, treat each other with respect, and where our beneficiaries are at the centre of all we do. This may not be happening at the moment. But aren’t we in the business of social justice and equity? Aren’t we dedicated to shining a light on what is missing and working for improvements? Systems clearly need to improve if we are to provide the best service possible for our beneficiaries. The third sector has agency. Let’s use it.

[1] Our relationships with power and our mental health are connected. Third sector leadership teams can be badly affected as Breaking Point’s: “The Mental Health Crisis in Small Organisation Leadership” reports. It identifies that 85% of small charity leaders in England experience poor mental health due to their role. The report makes recommendations which could make a significant difference to small organisations, aimed at individual leaders, small organisation boards and funders. You can find the report here: https://www.faircollective.co.uk/breaking-point-report